How to spot fake news

Have you shared an article, or told a friend a story, without double-checking the facts? If so, you could be responsible for spreading fake news. We find out how to spot it, and what can be done about it

Fake news is content that’s purposely created to misinform and mislead.

It’s been blamed for shock election results worldwide, is considered dangerous by global experts and can be difficult to spot. Many of us constantly receive, process and share information via our smartphones and tablets, so how do we identify what’s real and what’s ‘fake’?

Sense About Science is an independent charity that champions the use and understanding of evidence in public life. Alex Clegg, their Campaigns and Communications Coordinator, says, ‘In our day-to-day lives, we come across claims from politicians who want us to vote for them, and public bodies who want us to change our lifestyles. We say that if someone’s making a claim and asking you to change your behaviour as a result, you should be able to ask them for evidence.’

Sense About Science has released the Evidence Hunter activity pack, which aims to get young people asking critical questions about the information they see.

The pack was created with the help of local Scouts and volunteers, including leader Jane Sarginson. ‘As well as a Scout Leader, I’m also a Biomedical Science Lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University and a mental health researcher,’ Jane says.

‘So I get to see how important the ability to judge the quality of different information sources is to every aspect of young people’s lives.

‘We piloted the activities we developed with my own Scouts, which was an interesting experience for all concerned. They really liked the fact they were helping to develop something that other young people would use. But it scared me how much they believed, just because it was written on a bit of paper.

For Jane, the project is vital: ‘I think it’s important that young people become aware of fake news, because they’re bombarded with so many different sources that weren’t around when I was a kid.’

Fact or fiction?

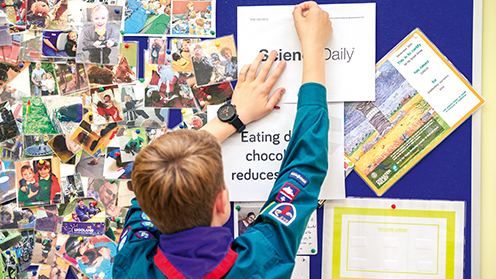

We wanted to see for ourselves what young people think about the news they receive, so we went to try out the Evidence Hunter pack with 1st Ely Scout Troop. Assistant District Commissioner and Section Leader, Caroline Spaxman, was kind enough to lead the session.

One of the first activities involves displaying five headlines around the room and giving everyone 10 ‘trust tokens’ each to distribute among the headlines, according to how much they trust each one. The headlines are: ‘Caffeine reduces premature hair loss’, ‘Using social media affects your sleep’, ‘Charcoal toothpaste whitens your teeth’, ‘Eating dark chocolate reduces stress’, and ‘Being kind to others makes you happier’.

Caroline announces the start of the activity and everyone races to the headlines. Immediately, debates break out. After about 10 minutes, the tokens are counted. Caffeine reducing hair loss has 20 tokens, charcoal toothpaste has 28, dark chocolate 35, social media 59, and being kind has a whopping 78 tokens.

Charles, aged 12, pipes up: ‘The “Being kind to others makes you happier” one is the most believable because it works for me!’ Lots of people agree: the ‘being kind’ headline is popular because it’s the Scouts way. Similarly, parents have told some of them that social media will stop them sleeping, so that one’s well trusted, but the caffeine and charcoal headlines sound suspiciously like beauty advice – which they trust less.

Next, the source of each headline is revealed: ‘Caffeine reduces premature hair loss’ is an advertisement from a shampoo company, Alpecin; ‘Using social media affects your sleep’ is from the Metro newspaper; ‘Charcoal toothpaste whitens your teeth’ is a claim from celebrity Nicole Scherzinger; ‘Eating dark chocolate reduces stress’ comes from ScienceDaily; and ‘Being kind to others makes you happier’ is from the University of Oxford.

A fresh set of tokens is given to each young person to distribute with the new information in mind. Again, there’s a scrabble and heated discussion.

The shampoo advert reveal is met with shrieks of laughter and its token pile remains small, with just a few of the young people wandering over to furtively drop a token. Finally, it’s time to come back to the centre for counting.

The verdict

It quickly becomes obvious there’s a huge amount of trust in the University of Oxford: the number of tokens for ‘being kind’ has more than doubled. ScienceDaily’s headline on chocolate has increased by a handful of tokens, and the Metro’s story on social media has dipped slightly. This source is divisive – some Scouts firmly trust newspapers, while others are more cynical. ‘I’d trust all of the newspapers equally – I think they’re all a bit biased,’ says Callum, 13. Jacob, also 13, disagrees. He says, ‘I wouldn’t trust the Mail – they make some really weird claims.’

The caffeine headline has just four tokens. Nobody seems surprised, and someone shouts, ‘We didn’t trust the caffeine one, because the hair people are making money from it!’

Now that everyone knows a celebrity is behind the charcoal toothpaste headline, it’s gained just four tokens.

Caroline shares the full sources with everyone and there’s a chance to assess them using the Sense About Science guidelines. Callum and Jacob are given the ‘being kind to others’ story, and agree it confirms what they thought. Jacob says, ‘I put my tokens on this one because Oxford is seen as a very good university, and here it’s been backed up by an in-depth study; there’s lots of information about how they did it.’ Callum adds, ‘How they’ve worded it is quite professional; they’ve used figures and they’ve laid out their method.’ The full Alpecin caffeine advert also seems to cement opinions. From across the hall comes an outraged, ‘It’s scientific gibberish! What does it even mean?’

The most controversial story is the one on charcoal toothpaste, which divides the room. Aaron, 12, jabs a finger at the smiling photo and says, ‘I trust the Nicole Sherzinger one most, ’cause look at those teeth!’ Even in the photocopy, they gleam icy white. His friend disagrees, ‘They could’ve just got their teeth whitened though. They’re probably being sponsored…’ Someone else pipes up, ‘It says their teeth changed from first use, but I don’t think it would.’

Alex, 12, has been studying the source for some time. Finally, he says, ‘It’s just one person’s opinion, and it might make them look whiter, but it could also damage them.’ The others nod in agreement. When asked if some celebrities are more trustworthy than others, Alex answers quickly. ‘Yeah… Steve Backshall. He knows a lot. And scientists, like Brian Cox.’

Joshua, 11, isn’t sure. He says, ‘If one of my friends on social media said something, I’d trust them. I’d trust them a lot more than any celebrities on social media.’ Alex replies, ‘Yeah, but I’d trust an expert celebrity more… like a blogger.’ The group start discussing their social media habits: who they follow and which channels they like. None of them seem entirely sure what’s public and what’s private on platforms like Instagram and Facebook.

Building digital citizens

Last month, Scouts launched a new partnership with internet tech company, Nominet. They commissioned research from experts Unthinkable on how we can make sure our digital citizenship programme is as relevant and useful as possible. Matthew Shorter, Director of Unthinkable, noticed similar discussions on privacy when visiting Scout groups for the research.

He said, ‘We ran a workshop in Lancashire, where I asked the young people how they thought social networks made money. It wasn’t something they’d given any

thought to.

‘I asked them, why do you think social networks are free? They talked about advertising, and we discussed the fact that lots of people use the networks, so they receive a lot of data – which has implications for privacy. While lots of young people have got the message that you need to control your privacy settings, they haven’t yet thought about whether social networks want them to do this: they might design their sites so that it’s hard to find the settings or difficult to change them. Lots of young people haven’t thought about these things on a business or political level.’

In Ely, while everyone seems aware that the internet and social media can be dangerous, no-one mentions limiting their use of it. Matthew explains, ‘There’s a set of terms, “digital natives” and “digital immigrants”. Digital immigrants are older; they didn’t have the internet or social media when they were younger so they see it as more of a separate entity and remember life before it. Digital natives are usually considered those born in the late ’90s onwards – they’ve grown up with the internet and social media being a normal part of life. It’s generally framed that digital natives are much more clued up, but actually, digital immigrants have got some advantages as well. They often have a much clearer understanding of how we got here, what different technology is for, and what life is like without it.’

Of course, it isn’t reasonable to expect people to completely avoid the internet, and it has lots of benefits: communicating with different people, accessing new information, even creating social change. We just need to prepare young people for the challenges it throws up.

After the session, Caroline says: ‘Before, I wasn’t sure if the group was going to take to it. I discussed it with them afterwards and they said it’s been really useful, because it’s made them realise you don’t have to trust the headlines. There are more sides to every story, and I’m impressed by how quickly they got that.’

Matthew agrees that education is important. ‘I think knowing how to process information online is less of a hard technology skill and more of a mind-set,’ he says. ‘To be sceptical – not cynical – and to ask the right questions about what we see online is vital. I think fake news has been going around for hundreds of years, and you couldn’t get rid of it without lots of negative side effects around freedom of speech. You just need to educate people about it.’

Three top tips for spotting fake news from Sense about Science

1. Look at the source

Who’s making the claim? Is it a celebrity, a company or an academic journal? From there you can begin to work out where the claim has come from, and whether there’s any evidence.

2. Ask questions

Does that source have any vested interests? Are they making money from it? Are they selling something? Why are they making this claim? It doesn’t always mean the claim is dubious, but it’s a good place to start. It’s particularly important for channels like Instagram, where lots of celebrities get paid to promote a product. They won’t necessarily look at the evidence, but they’ll say that it’s effective for a fee.

3. Evaluate the evidence

Has it been peer reviewed: have other academics read it and agreed with the claims the study is making? Is it just one study, or have multiple studies proven it? Sometimes it’s one sensational case that the newspapers are talking about, rather than something that’s been subject to different studies, which the scientific community generally agrees upon.

Download the Evidence Hunter pack: scouts.org.uk/evidencehunter. Learn about our partnership with Nominet here https://fundraising.scouts.org.uk/nominet.

You can download Scouting Magazine here.