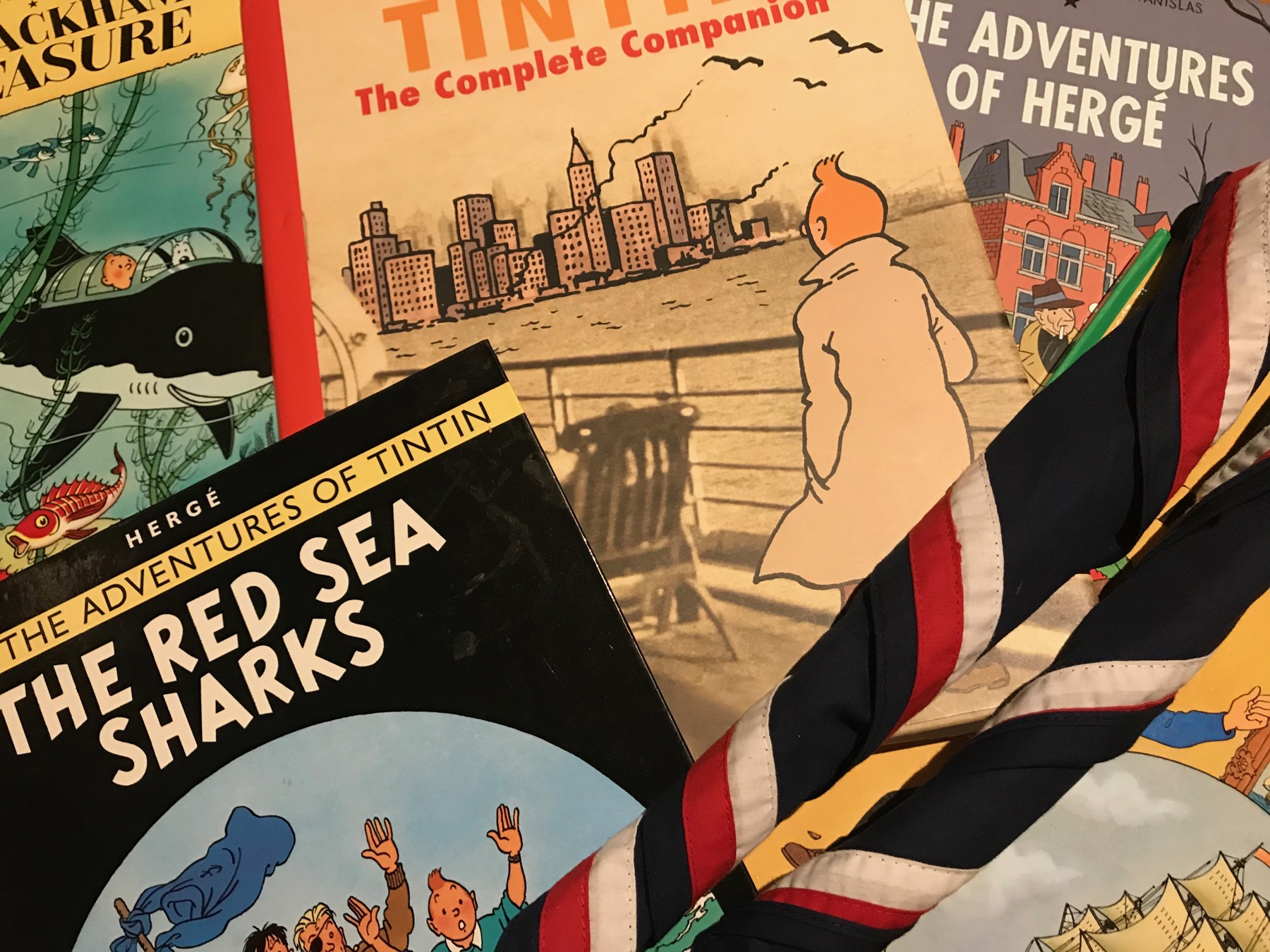

The mystery of Hergé, Tintin and the Scouts

In 2007, an extraordinary discovery was made in a disused Scout hut in the grounds of a school in Brussels. On the chipped and peeling walls were a series of murals: muddy-brown figures of Scouts, life-like and skilfully drawn. But this was no graffiti – it was some of the earliest ever known work by Hergé, creator of Tintin.

The year 1907 saw the birth of two cultural phenomena, both of which went on to capture the imagination of the world. One of course, was the Scout Movement. The other was a man: Hergé, the brilliant graphic artist whose documentary style propelled him to the sort of fame never before enjoyed by a ‘mere cartoonist.’ But this date wasn’t the only thing they shared.

An inquisitive child

While Baden-Powell was running his experimental Scout camp on Brownsea Island, Hergé (or George Remi as he was christened – the penname comes from the French pronunciation of his initials in reverse) was just starting out in his native Belgium.

By his own admission, George was a quiet child, ‘sometimes reserved but always shrewd.’ These qualities stood him in good stead at school, where he was well liked without being the centre of attention. ‘My childhood seemed to me very grey,’ he said in 1973. ‘Of course I have memories, but these do not begin to brighten, to become coloured, until the moment I discovered Scouts.’ It is clear that the adventure he found in the Movement - still barely a decade old - brought out something wonderful in the young artist.

Hergé’s first adventures

Hergé’s Scouts story began when he joined the Scouts of Belgium in 1919, where his talent for observation, love of wildlife and the outdoors first had an outlet. He only really came into his own when, at the age of 13, he joined his school Troop at St. Boniface’s. The Troop was ahead of its time, in that it encouraged Scouts to cross borders and strike up international friendships.

His new friends in Scouts were impressed by his grasp of traditional skills, such as knot-tying and pioneering and he took great delight in sharing them. Such skills came in useful for their regular trips into the country and beyond. George and his fellow Scouts spent three weeks in 1921 travelling through Switzerland, Italy and Austria, affording him his first glimpse of foreign cultures and contrasting political situations.

A habit for art

Before long, George never left for camp without first packing his notebook. In it, he would record the sort of observations that would become the source material for the Tintin adventures. It’s also early evidence of Hergé’s lifelong habit of squirreling away details for later use. A sketch of the St. Boniface Scouts roped together on a 1923 expedition climbing in the Pyrenees for example, would later be transformed into an illustration for the 1959 adventure Tintin in Tibet. ‘The Pyrenees,’ he said many years later, ‘discovered with the St. Boniface Scouts, was the Tibet of my youth.’

His first break as an artist

As well as providing Hergé with a love of the outdoors and a practical primer in geography and politics, Scouting was also responsible for his first break as a professional artist. Known to be an accomplished cartoonist, he was coerced by his fellow Scouts into providing illustrations for Never Enough, the St. Boniface Scouts’ magazine. It was around this time that he also completed the now famous murals.

So impressive were the results that they caught the eye of Rene Weverbergh, the Scouter responsible for the Brussels Scout District. Before he knew it, at the age of 17, George had landed himself a job on Le Boy Scout (later the Le Boy Scout Belge) - the national magazine.

Hergé, ‘the Curious Fox’

As his career as an artist was finally taking off, George’s skills were also gaining recognition in his Scout Troop. In 1923 he became Patrol Leader of Squirrel Patrol, assuming the name Curious Fox. It was a fitting moniker for a young man with such a tireless interest in the world around him.

Remi was a natural leader, with a quick sense of humour, a gift for inspiring younger Scouts and an insatiable appetite for adventure. As a measure of how much he savoured his new role, he began signing off his cartoons with ‘the Patrol Leader Curious Fox.’ At this point of course, Tintin himself was still a little way off and it was the quirks of Scouting life that populated his strips, but Hergé was about to take a step closer to the famous reporter with the introduction of a brand-new character.

Totor: the prototype for Tintin

Totor, an adventurous Scout Patrol Leader was clearly modelled on Remi’s own experiences and was to be the prototype for Tintin. Not only did he bear a passing resemblance to the young reporter, he was also accompanied by a faithful canine companion. Totor was a great success with adults and young people alike and was to run until 1931 when for a time, he and Tintin existed side by side.

While illustrating for Le Boy Scout Belge was a prestigious slot, it was not a living. Now, having completed his diploma it was time for Remi to find himself a paying job. Again, his patron Rene Weverbergh stepped him and recommended him to the daily newspaper Le Vingtieme Siecle (‘The Twentieth Century’). Like many graduates, he found his first job to be far from glamorous - working in the subscriptions department. It was not until he returned to the paper after a spell of national service that his career as an illustrator really began.

An international phenomenon

By the time Tintin made his first appearance in the paper’s supplement, Le Petit Vingtieme on 4th January 1929, Hergé had served his apprenticeship. Tintin in the Land of the Soviets was the first of 24 adventures that would take the reporter to South America, Tibet, Egypt and even the Moon. By his last, incomplete adventure – Tintin and Alpha Art – Hergé was published in 60 languages.

Tintin is the archetypal Scout. He is practical, resourceful and has a hundred skills up his sleeve, from improvising a sling to locating water. He is a master of disguise, an excellent swimmer and even on one occasion uses his knowledge of astronomy to get himself out of a particularly difficult fix in Prisoners of the Sun. ‘Take care of that newspaper,’ he says to the Captain in the same adventure, ‘we might need it to light a fire.’ Above all, it’s his firm sense of moral purpose, championing the cause of the weak, as well as being a loyal friend, which marks him out as the ideal Scout.

Fond memories

The Tintin adventures would go on to sell 120 million copies, making Hergé a wealthy man, but he never forgot his days as the intrepid Patrol Leader, Curious Fox. Even in old age, Hergé retained his affection for the movement, allowing Scouts and Guides to camp in the grounds of his Belgium mansion - impossible to imagine as anything but Marlinspike Hall, the country seat of Captain Haddock. He would wander down to the camp, ask questions about the activities and share his own Scout memories.

‘As a young man, Scouts was Hergé’s main preoccupation; even passion,’ says Michael Farr, a world authority on Tintin. ‘Its code, principles and enthusiasm were his and were to be embodied in Tintin, as much a Scout as a reporter.’

But we should give the final word to Herge himself: 'Scouts gave me a taste of friendship, love of nature, animals and games. It is a good school.'