Jack Cornwell

On the 31 May 1916 the actions of an ordinary boy in extraordinary circumstances led to the development of Scouting’s Cornwell Badge. This badge is still awarded by The Scout Association to honour those Scouts under 25 years of age who demonstrate a pre-eminently high character and devotion to duty, together with great courage and endurance.

Early life

The ordinary boy was John Travers Cornwell, known as Jack. Jack grew up in Leyton and Manor Park in North East London. He came from a large family with five siblings, his Father, Eli Cornwell, had previously served in the Army. Jack joined his local Scout Troop at St Mary’s Mission, Little Ilford. In common with today’s members Scouting taught Jack new skills and he gained recognition for his work.

His Scoutmaster later recollected: 'Nothing was too hard for him… …he would attempt any task. After passing his Tenderfoot he worked for his Second Class which he eventually won, and kept the pot boiling by passing his Missioner’s Badge.'

Unfortunately, in common with many other boys, Jack’s Scouting career was cut short by the outbreak of the First World War; the leaders joined up, and the troop was dissolved. By this point Jack had left school and was working as a delivery boy.

Naval career

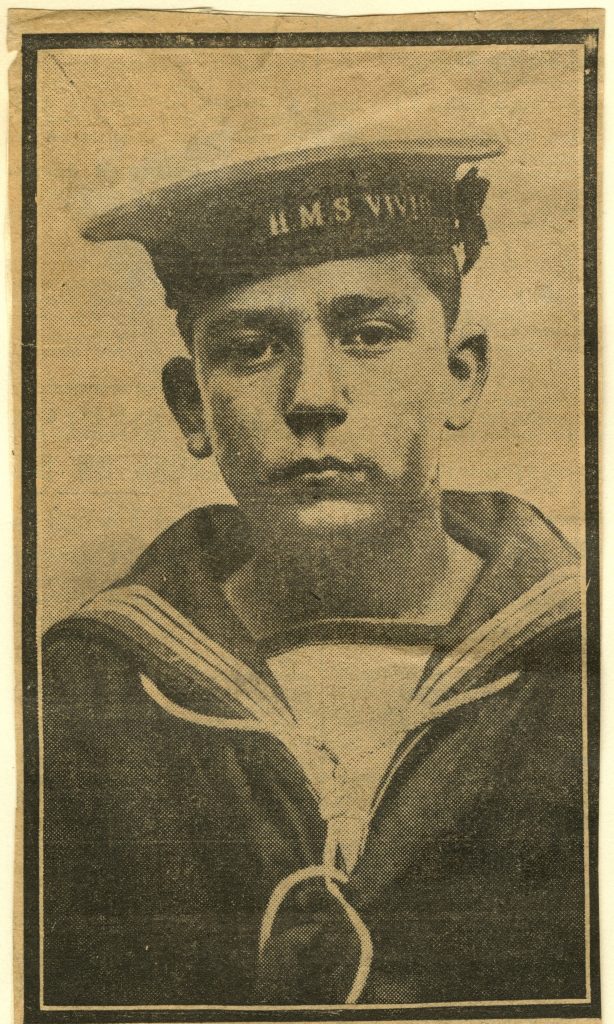

During the first few weeks of the War recruitment fever had swept the nation and Eli Cornwell re-joined the Army serving with the Royal Defence Corps. At 15 Jack would have been too young to follow his Father into the Army as the recruitment started at 18 years. He was, however, eligible to join the Navy which he did. His service record shows he was 5 feet 2.5 inches tall with brown hair, blue eyes and a fresh complexion.

Having already shown an aptitude for learning new skills in his Scout troop he appears to have taken to Navy life and progressed well with his training. Initially based at HMS Vivid in Plymouth Jack was then transferred to the training ship HMS Lancaster.

He was taught the additional and more complex skills of a Sight Setter meaning that he would be tasked with setting the direction and elevation of a gun on a warship. In April 1916 he completed his training with the rank of “Boy – 1st Class” and was assigned to HMS Chester. The timing was critical, the newly trained Jack would be part of the most crucial Naval engagement of the First World War, the Battle of Jutland.

The Battle of Jutland

HMS Chester was part of the British Grand Fleet under the command of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe and on the 30 May 1916 the Grand Fleet left its base at Scarpa Flow in the Orkney Islands off Scotland. The Battle Cruiser Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty was already further south in the North Sea. In the early afternoon of 31 May the German Fleet was sighted by Beatty and his fleet and shortly after the Battle of Jutland began. Jellicoe sent a Battlecruiser Squadron, including HMS Chester, ahead of the main part of his fleet to seek out and support Beatty’s fleet. Jack would have been stationed by his gun wearing headphones so he could hear orders from the Gunnery Officer.

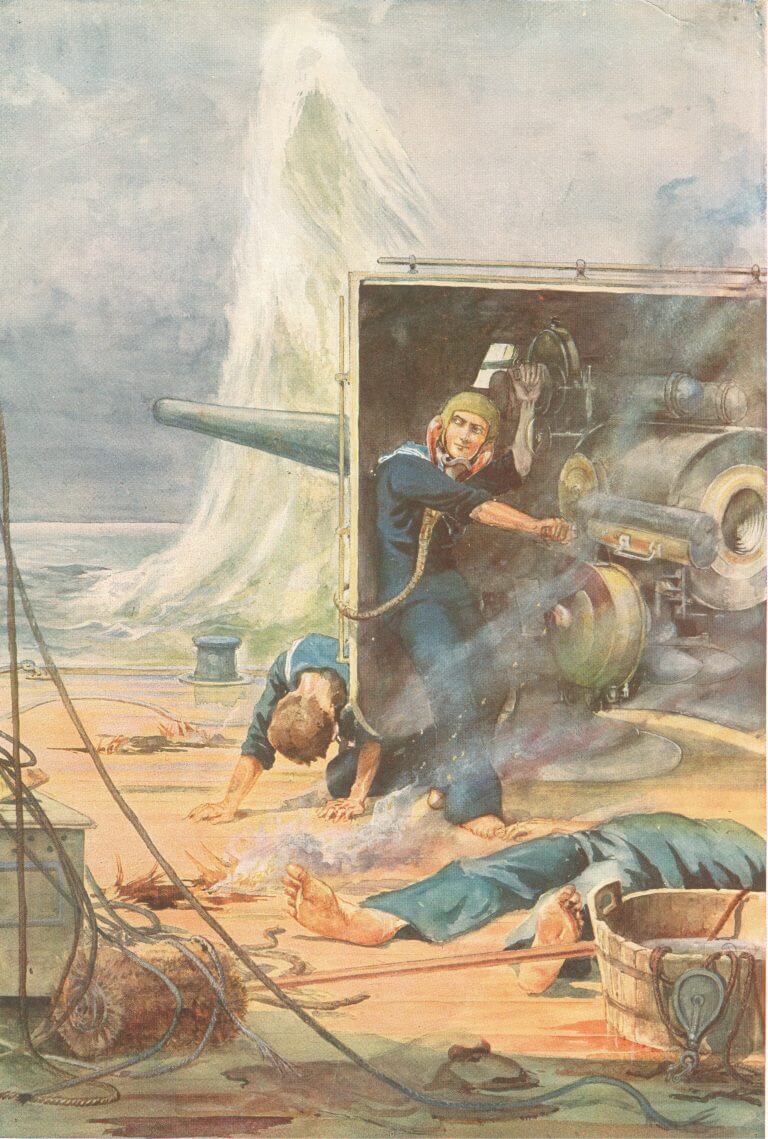

On receiving instructions he would then have to set the gun sights enabling it to be accurately fired. About two hours into the Battle HMS Chester came into the action and was heavily pounded by four German ships receiving 17 direct hits in the first few minutes. Jack’s gun was near the front of the ship and was hit early on. With many of his shipmates dead or badly injured Jack was left as one of the few men still standing.

He had received a serious wound, but his behaviour over the next few hours showed his devotion to duty and courage in the face of adversity.

His Captain later wrote to Jack’s mother, Lily Cornwell, describing what happened next: 'He remained steady at his most exposed post at the gun, waiting for orders... But he felt he might be needed, and, indeed, he might have been; so he stayed there standing and waiting, under heavy fire, with just his own brave heart and God’s help to support him.'

Following the Battle Jack was transferred to the Grimsby and District Hospital but it was apparent that nothing could be done to save him and he died on 2 June 1916.

His mother was sent for but sadly couldn’t reach Grimsby in time to say to goodbye to her son. His death certificate reads: “Intestinal perforations due to wounds received in action. Injuries received in the naval battle between the British and German navies in the North Sea.”

Funerals

When a member of the armed forces dies the service will pay for the grave and funeral. This would have certainly been offered for Jack and would have taken place in or near Grimsby. However, it appears that Lily Cornwell, wanted a private funeral and arranged for his body to be brought back to London where it was buried in a common, shared, grave in Manor Park Cemetery. Jack’s Captain speculated that maybe due to her grief Lily hadn’t understood that the Navy would pay for a grave and funeral but it may be that she wanted her boy close to home or couldn’t face the formality of the military service. However her grief was not allowed to remain private for long.

The story of Jack’s bravery captured the public imagination, it had been briefly mentioned in Vice Admiral Beatty’s report of the Battle. With the second year of the War drawing to a close, stalemate on the Western Front and the news from Jutland not as overwhelming positive as might have been expected the British public were looking for hero. As Beatty’s report was published the act of this ordinary boy became headline news. Campaigns began to have Jack’s bravery properly commemorated, there was outrage that this national hero did not have his own grave. On the 29 July 1916 Jack was reburied with full military honours in a private grave at Manor Park Cemetery. The funeral was preceded by a spectacular procession with hundreds of Scouts lining the route and members of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve pulling the gun carriage on which rested the coffin.

Bravery recognised

Jack’s commitment to his duty and comrades and strength in the face of adversity lead to his nomination for a posthumous Victoria Cross, the highest military decoration awarded for valour 'in the face of the enemy'.

Vice Admiral Beatty wrote: 'The instance of devotion to duty by Boy (1st Class) John Travers Cornwell who was mortally wounded early in the action, but nevertheless remained standing alone at a most exposed post, quietly awaiting orders till the end of the action, with the gun’s crew dead and wounded around him. He was under 16½ years old. I regret that he has since died, but I recommend his case for special recognition in justice to his memory and as an acknowledgement of the high example set by him.'

King George V endorsed the award and Lily Cornwell was invited to Buckingham Palace to receive the Victoria Cross on behalf of her son. Jack’s was one of four Victoria Crosses awarded for bravery at the Battle of Jutland.

Jack’s bravery was also recognised by the Scouting community, he was awarded the Bronze Cross, the highest medal for heroism which could be bestowed on a Scout.

Commemoration

There were only two contemporary images, both photographs, of Jack. Both images show him in his Navy uniform one wearing the hat of HMS Vivid and the other of HMS Lancashire. With such a public demand for his story his image was recreated several times. There appears to have been a strong family resemblance between Jack and his brothers and they stood in for Jack to satisfy the demand for new images. This included modelling for the artist Frank O. Salisbury who created an iconic image of Jack in the midst of battle standing at his post. Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Scouts and a talented artist also created a portrait depicting this scene. He sent his rough sketches to the Captain of HMS Chester to check that the planned picture would be an accurate depiction.

Several Memorial Funds were created in Jack’s memory, in August 1916 Baden-Powell announced the creation of a scouting Cornwell Memorial Fund to support Scouts with scholarships and apprenticeships. Funds were also raised to create a “Jack Cornwell Ward” at the Star and Garter Home, Richmond, for injured servicemen. Jack’s image appeared on postcards, cigarette cards and a poster was produced to be displayed in classrooms.

A source of inspiration

Jack’s story was used to inspire young people to emulate his sense of duty and courage. A Jack Cornwell Day was held in September 1916 for schoolchildren to reflect on his achievements. In Scouting it was felt that an award to honour the highest achieving Scouts should be created in his memory. A recipient should not only have reached the highest standards in his Scouting career but also have performed an act of bravery which saved a life or have undergone suffering in a heroic manner. The design of the badge was a bronze C (for Cornwell and courage) encapsulating the Scout emblem.

The first Cornwell Scout

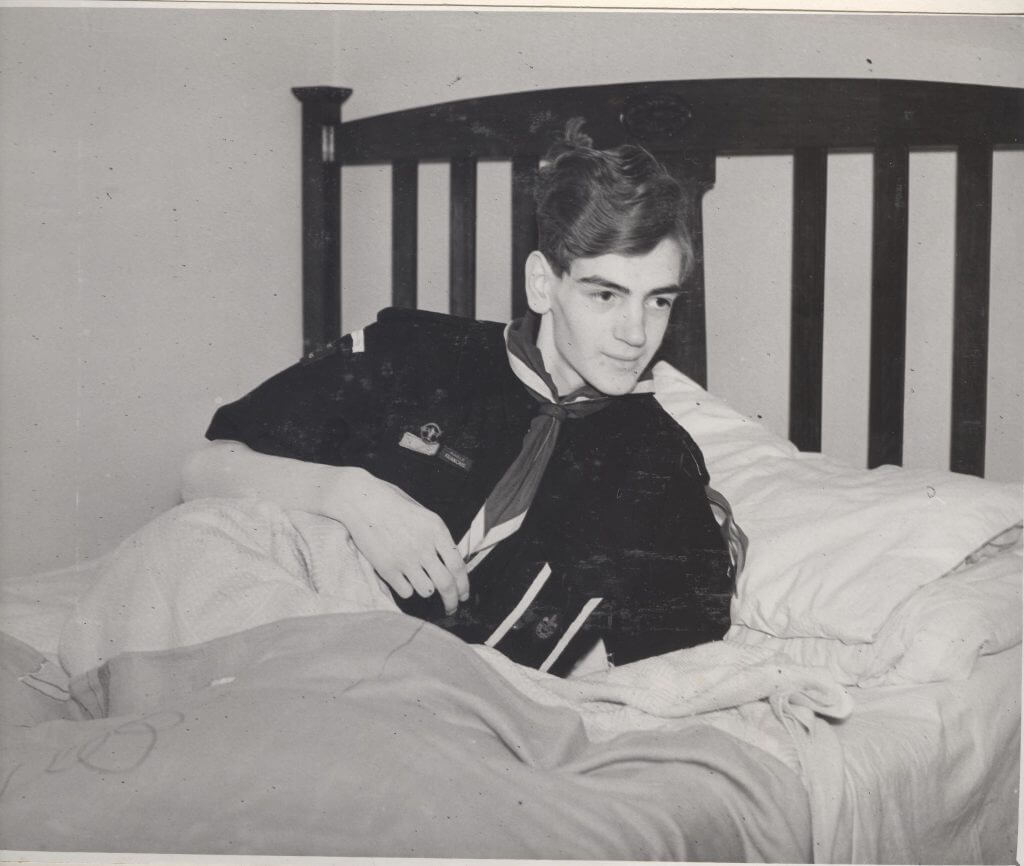

Arthur Shepherd’s 15th birthday was not one he was going to forget. Arthur was a Scout with 8th Middlesbrough (St Paul’s) Troop.

Arthur and his patrol were supporting the Coastguard in Whitby with the coastwatch when on the 30 October 1914 the hospital ship Rohilla hit a reef just off Whitby. For three days the Coastguards and Scouts worked to rescue the drowning men and recovering bodies.

Arthur took on the most dangerous job of bringing supplies of rockets from the Coastguard station and relaying messages, as described in the December 1916 Headquarters Gazette: 'In doing this he had to make his way along the face of the cliff by a very narrow and slippery ledge of rock which overhung the sea and was washed by the waves. He had to do this alone, with a gale blowing, and in the dark, when a false step or a slip meant death. But he did it, and did it several times.'

This wasn’t Arthur’s only act of bravery, a matter of weeks after the Rohilla sank Whitby was hit by a German Naval Bombardment. Again Arthur and his fellow Scouts went to support the Coastguard and the community of Whitby.

On 1 December Baden-Powell attended a special rally in Middleborough. Around 3000 boys attended with members of the Scouts, Boys and Church Lad’s Brigades. Baden-Powell presented Arthur with the very first Cornwell Badge. It really was the very first as the only one in existence at that point was the factory sample, so this was retrieved from the manufacturers for use at this special occasion.

The Cornwell Badge

There is an irony that the standards set for the Cornwell Badge in 1916 meant that Jack Cornwell couldn’t have won the badge as he hadn’t attained his First Class Scout award. Rapidly the emphasis was placed on the requirement to '…have undergone suffering in a heroic manner' and many recipients of the award are Scouts who have carried on Scouting despite suffering from long-term or terminal illnesses. The award citations show that these Scouts often belonged to Groups associated with hospitals.

The criteria have changed several times to reflect the changing nature of the Movement. In 1935 need for a high level of achievement was dropped and the basis of the award became closer to today’s criteria focusing on '…pre-eminently high character and devotion to duty together with great courage or gallantry'.

The badge was normally only awarded to Scouts over the age of 14 years. There were exceptions to this rule and in 1939 the first two Wolf Cubs were presented with the Cornwell Badge. Over the next six years nine more Cubs were presented with the badge and in 1945 the age recommendation was changed to Scouts under the age of 18 and then to all members of Scout sections (Beaver, Cub, Scouts, Explorer and Network) which now covers 6 – 25 year olds.

100 years on from Jack Cornwell’s heroic behaviour The Scout Association still honours young people in his name and the core values that Jack’s story embodied; selflessness, devotion to duty, commitment to others and strength in the face of adversity, remain as important to the Movement as they did then.